The plan according to which the Plano Piloto was built didn't only include positions of buildings and roads but focused on how people would be using the created places as well. In this modernist city, living and working should not be mixed and the residential areas were therefore carefully planned. The plan included a detailed structure on where and how the inhabitants were supposed to design their everyday life regarding supply systems, medical care, educational institutions, faith sites and sports facilities (Madanelo 1996). We asked ourselves to what extent the implementation of care for the people of Plano Piloto corresponds to what was initially planned. To put the study in a broader context, a comparison is made with the supply structure in Águas Claras. Thus, the question, where are the similarities and differences in the supply of different areas within the Distrito Federals will be answered.

Supply Offer

How was the local supply planned?

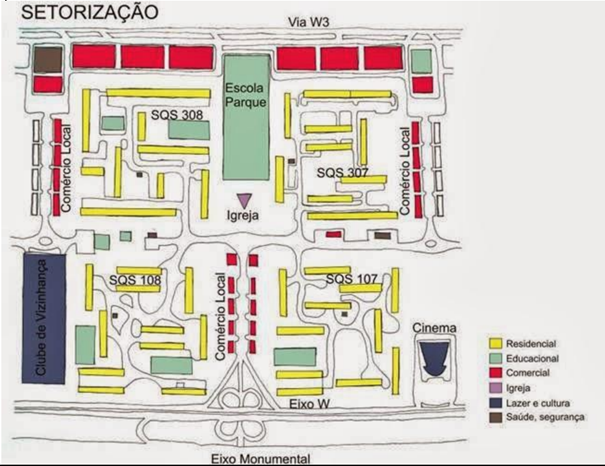

In contrast to the largely unplanned settlements of the satellite towns, in Plano Piloto, especially in Asa Sul

and Asa Norte, there were plans for the local supply of the residents. In the so-called Superquadras or

rather in

the communities of four Superquadras, the Unidade de Vizinhança, there were schools, medical

facilities,

playgrounds, clubs, swimming pools, gyms, as well as small stores with local supply possibilities (Madanelo 1996).

Most of the supply was to be covered by small local commercial areas, such as bakeries and butcher shops (Tattara

2011). These are located in the Comércio Local.

This idea is underlined by the geographer

Prof.

Aldo Paviani saying that one Comércio Local should host everything, from a butcher shop to a shoemaker.

A Comércio Local is always located between the two adjacent Superquadras. So, in principle one

Unidade de Vizinhança has three Comércio Locais at its disposal (see Figure 6).

The video on the left side shows an overview of an Comércio Local in Asa Norte. The shops are located in separate squared buildings all around the building. Most of the Comércio Locais in Asa Norte are similar to this one. The Comércio Locais in Asa Sul are build differently. These consist of continuous buildings on each side of the road with few passages to get to the other side of the building.

A very closely related theory is Walter Christaller's theory of central places. It deals with consumption and

spatial planning. Basically, the theory describes how an area-wide supply of the population with goods can be

implemented in the shortest possible distances. It explains how supply centers are formed and how they relate to

each other. The theory is based on the homo oeconomicus approach. Accordingly, a person always possesses all the

information and favors the offer that makes the most sense (Popp 2020).

What does local supply look like today?

Compared to the 1960s, when life in Plano Piloto began, society and especially consumer behavior changed

drastically. Even in Plano Piloto, today's supply structures look different to some extent. In order to determine

the current local supply structures, the method of mapping was chosen.

With this method, the current structures of the local supply system could be traced. The mapping evaluations show

that the Comércio Locais are still present and used. In addition, there are shopping centers that residents

use.

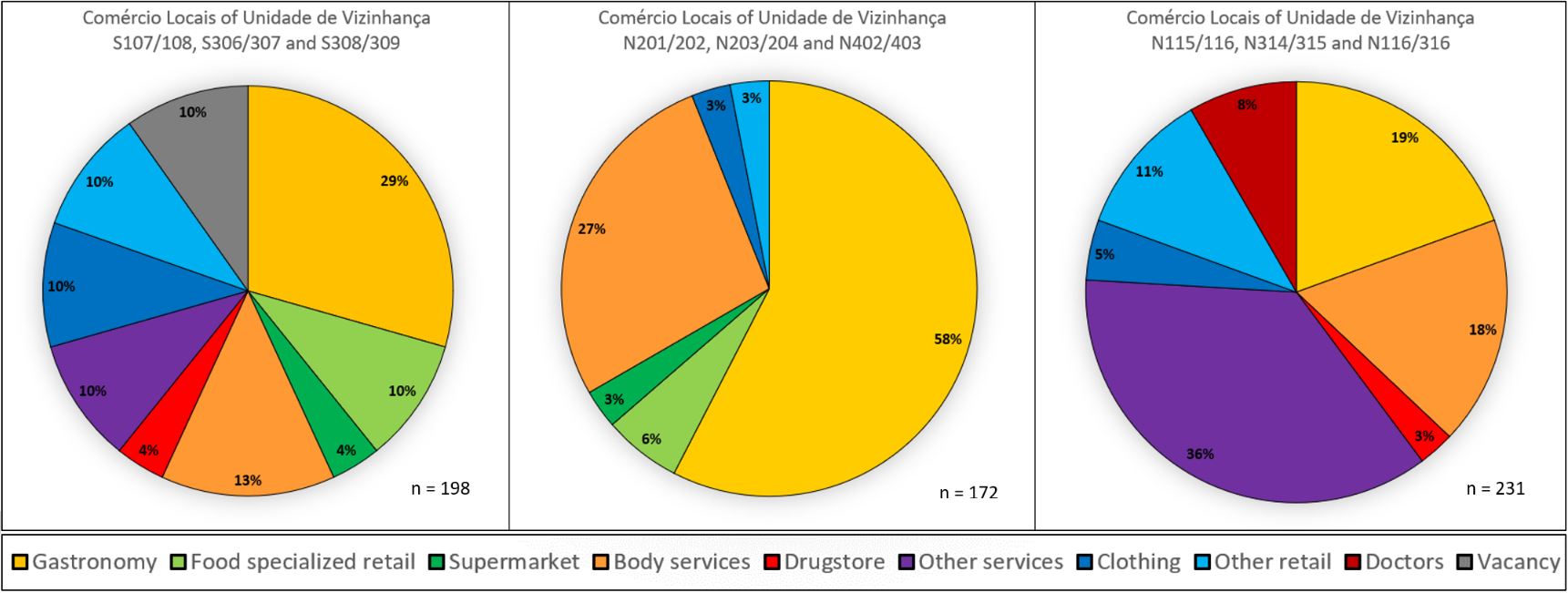

The Comércio Locais differ from each other in their specialization. Some Comércio Locais focus on

clothing,

specialty items or restaurants, while others are mainly heterogeneous.

The analysis of the Unidade de Vizinhança 107/307 & 108/308 Sul, for example, shows that clothing and other

retail

dominate (see figure 2). Meanwhile, in the Comércio Locais in the Unidade de Vizinhança 202/402 &

203/403 Norte,

most shops hosted bars and restaurants, with a non-negligible share of body services, such as hairdressers or

beauty salons. For the third Unidade de Vizinhança (see figure 2), gastronomy and body services occupy an

essential share of the commercial space. However, the major part is occupied by other services, which may be very

different from each other. This category includes language or dancing schools, fitness centers or estate agencies.

Another observation that can be made is that the share of food specialized retail or supermarkets is not

represented, as they are scarce in these Comércio Locais. Nevertheless, all the mapped Comércio

Locais present a

specific diversity within their range.

In addition, it could be determined that the condition of the Comércio Locais differs. Based on the

restaurants and stores' price range and the vacancies, the economic position of Comércio Locais can be

concluded.

During the mapping of the different Comércio Locais, we could observe that they were not the only spaces

that

hosted commercial activities, but that there were also shops along the Via W2 and the Via W3. These two streets

extend from south to north in Asa Norte and Asa Sul.

What has changed?

In summary, it can be noted that the local supply system has changed a lot, but in Plano Piloto, the basic

structures have been preserved until today. The Comércio Locais can still be seen as supply centers,

following the

central places theory, with the shopping centers increasingly competing concerning specialized retail. The

economist Alexandre Brandão Costa, who we were able to talk to mentioned several times that big supermarkets,

so-called Hypermercados, have become very important and that many people get their weekly groceries there.

The

range of services offered within the Comércio Locais varies greatly, but essential services are still

available in

each of the Comércio Locais we studied. It was also noticeable that there was no economic disparity in more

distant Comércio Locais. Vacancies could be observed in nearly every Comércio Local, but only in

some it there

were numerous enough to show on our graph.

In conclusion, the supply offered in Plano Piloto has increased, specialized in some places and is increasingly

controlled by the shopping centers. In addition, the importance of supermarkets, which now bundle most of the

local supply, has changed considerably. Every Unidade de Vizinhança has at least one larger supermarket. Here, the

results of our analysis overlap with those of Bezerra and Agner (2021). Following our hypotheses, it can be stated

that long-term planning of the local supply with a general master plan is not possible and is strongly influenced

by social and economic dynamics. Furthermore, it has been shown that the supply structure within Distrito Federal

is very heterogeneous. See here the supply in the

satellite town of Águas Claras.

Supply Demand

We've already learned about the supply structure in Plano Piloto and how it has changed. The following section

will focus on how the inhabitants use this supply offer.

Besides looking at the development of the supply structure in Plano Piloto, a second focus was set on the

demand of inhabitants concerning the main supply. This includes for example, where and how inhabitants of Plano

Piloto are going grocery shopping, having lunch, and doing other basic supply activities nowadays. Therefore, two

different methods were practiced: questionnaires and tracking.

Using the answers to the questionnaires, four different categories can be formed. The first question focuses on

the type of market that people go to for grocery shopping. Even with only six people participating, various

locations can be determined. This includes local organic markets, weekly organic fairs, bakeries, shops in the

nearby Comércio Local, supermarkets and even wholesale at Hypermercados. The participants chose these locations

based on quality, price, availability of parking spots and short distances to their apartments. Regarding where

the participants are having their main meals, the answers range from eating at home, cooking at home, and taking

it with them during the day to fast food, eating at restaurants depending on the day and using the cafeteria at

the university. Most participants rarely order their food online, saying: "only if time is short," "only if money

is left," or "only out of convenience."

By drawing a mental map, the participants were asked to display where they are buying their supplies in relation

to their home, how they move between shopping and home, and how much time it takes them to get to different

places.

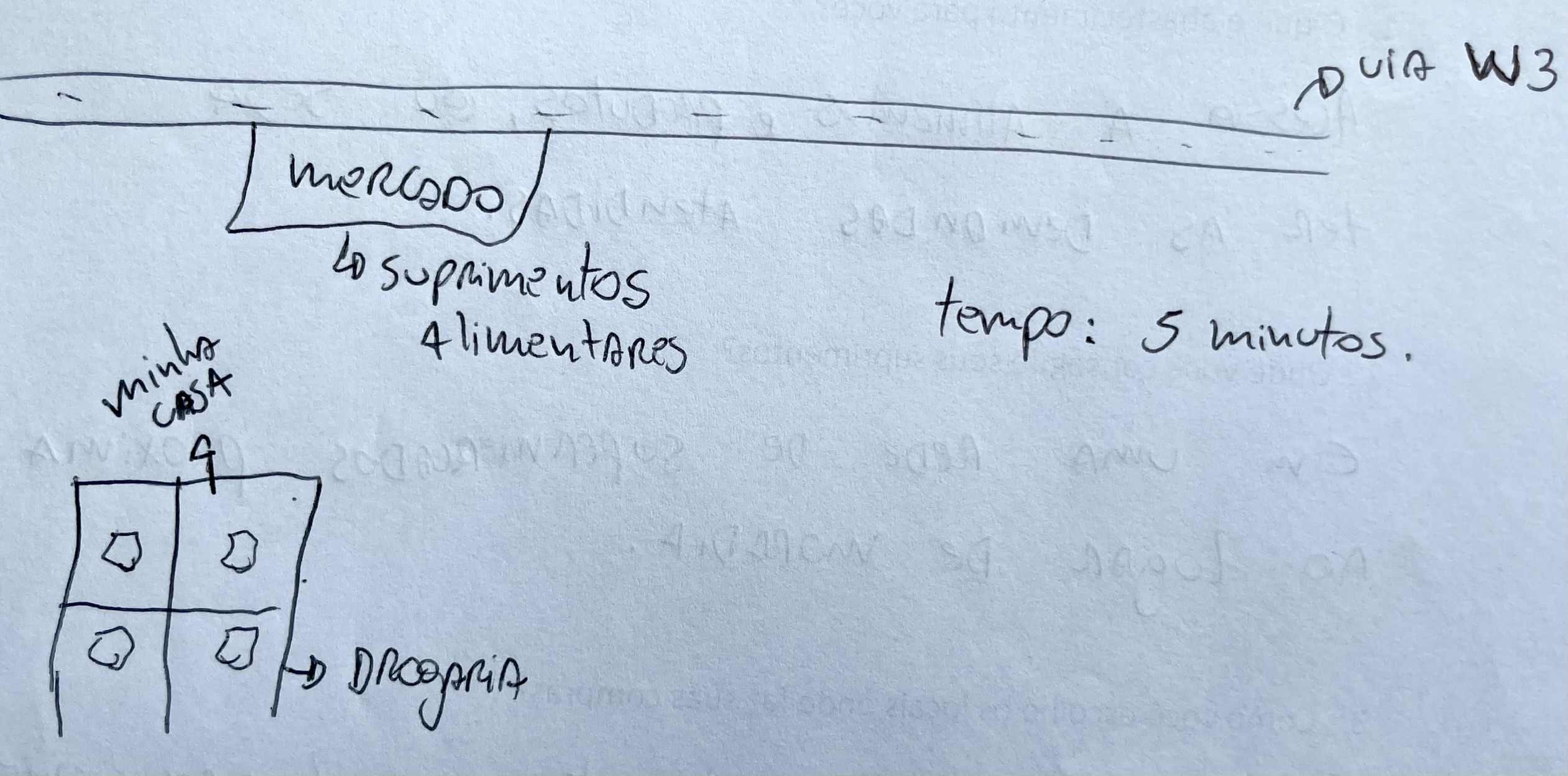

Figure 3: Mental Map 1. Source: own figure

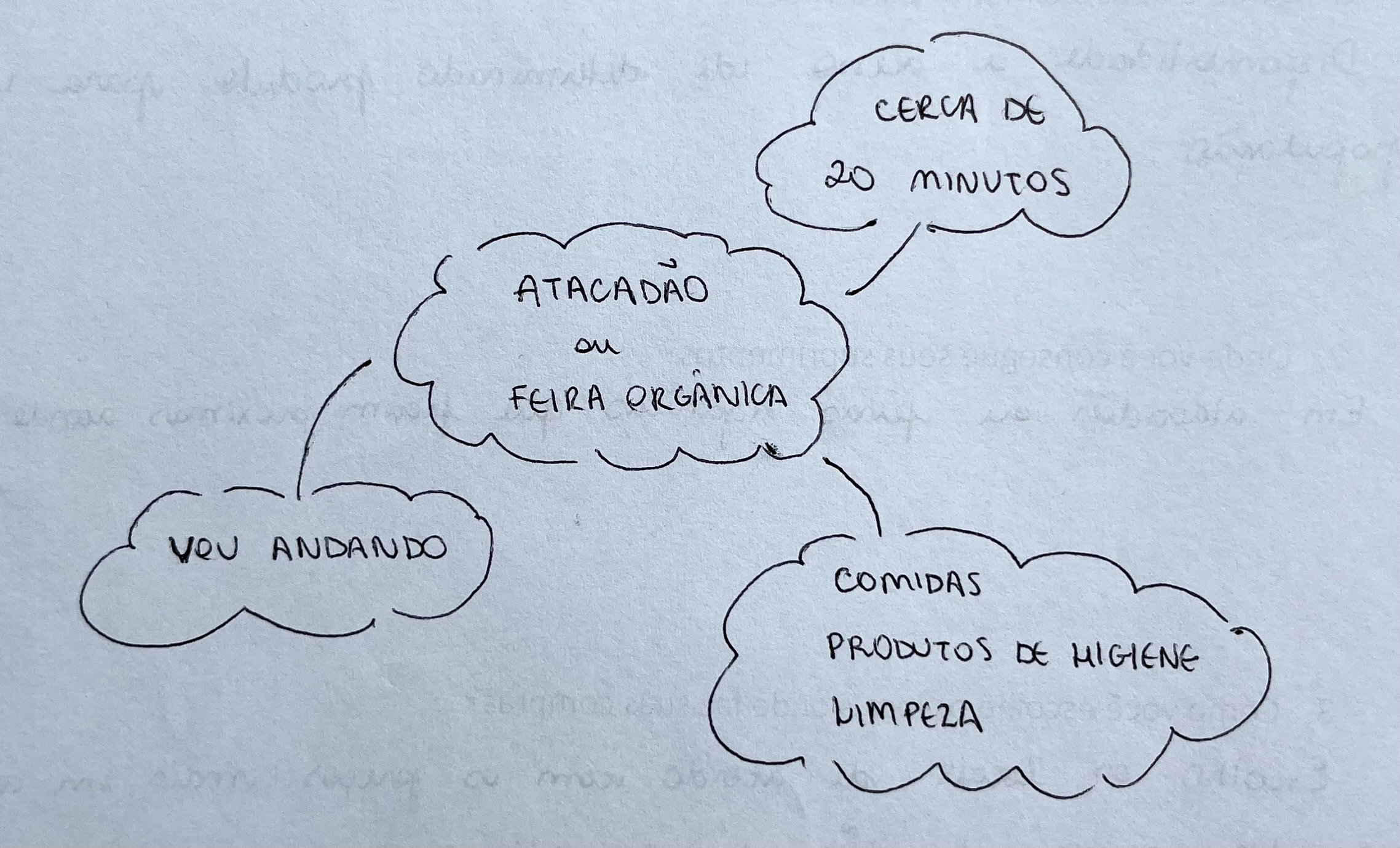

Figure 4: Mental Map 2. Source: own figure

The mental map in figure 3 presents that the person is living in a building where it takes 5 minutes to get to a supermarket and 5 minutes in the opposite direction to get to the chosen drugstore.

The mental map in figure 4 shows the name of a Hypermercado "Atacadão" and organic fairs in the middle of the map as the primary focus. The cloud in the top right corner shows that it takes the person about 20 minutes to get to the shopping places. The cloud on the bottom left side says that the person is covering the distances on foot. In the cloud in the bottom right corner types of products are listed such as food, hygiene products and cleaning supplies.

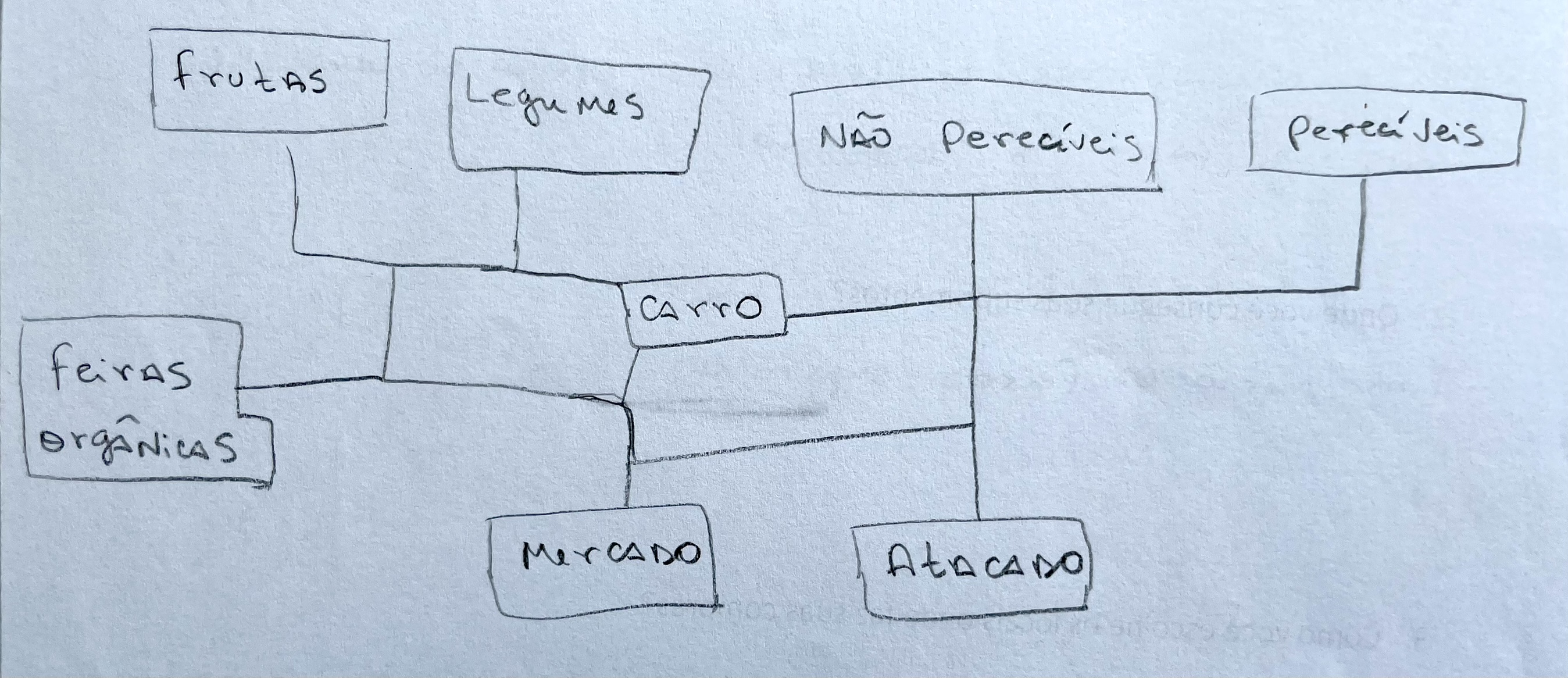

Figure 5: Mental Map 3. Source: own figure

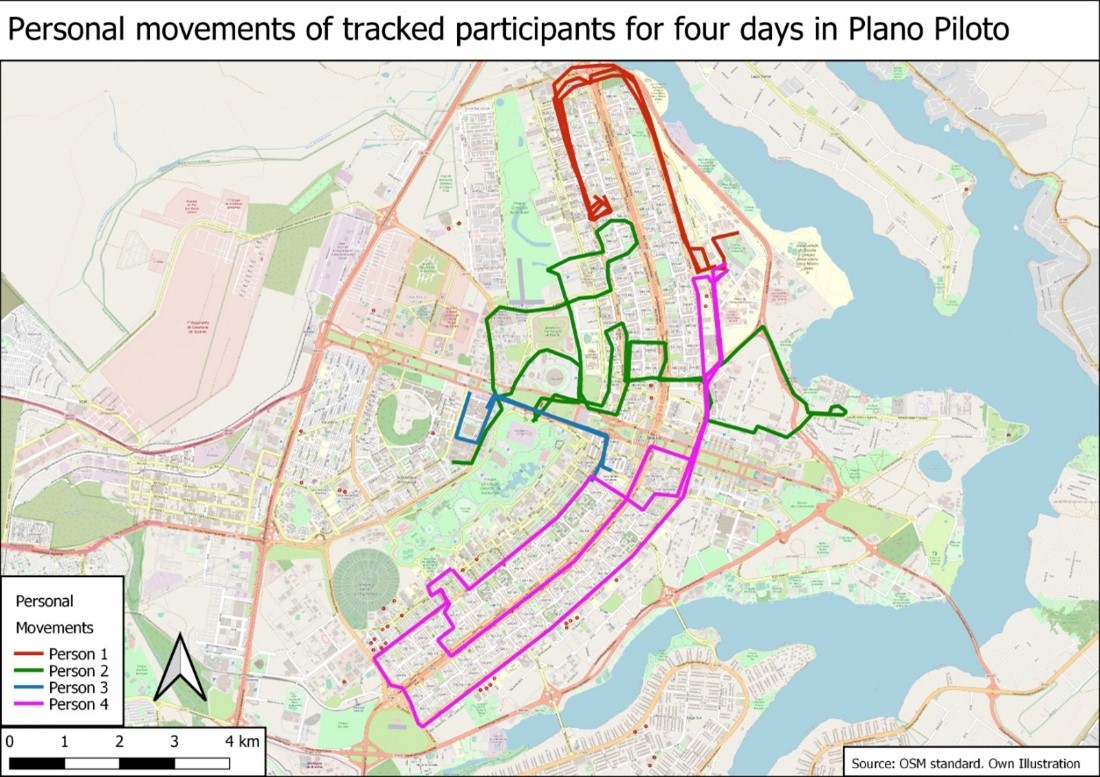

The mental map in figure 5 shows the word carro in the center as a focus which means car. All words around this (fruits, vegetables, organic fairs, supermarkets, Atacadão, perishable and non-perishable food) are connected through the word "car." This indicates regular usage of a car to purchase supplies. Through the tracking method, the idea that was already given by the mental maps could be stated more precisely. Four participants tracked their everyday life for four days with an app called Strava on their Smartphones. This method aimed to see how far and where people living in Plano Piloto are moving during their everyday life to accomplish everything necessary. The following map (see figure 6) shows the routes of all four participants. The fact that none of the participants left Plano Piloto during the tracking is very striking. The green track of person 2 has the most diverse route, whereas the red track of person 1 is mainly commuting between two different areas of Plano Piloto and seems to be moving by car. The pink track of person 4 is the only one moving in between Asa Sul and Asa Norte. This person also seems to be moving by car due to long distances and straight tracks along main roads. The blue track of person 3 shows a minor movement. If you want to know more about the mobility of people in Plano Piloto, click here.

What has changed?

Let us start with what has stayed basically the same so far. Considering the participants of questionnaires and tracking, it seems that the Comércio Locais still have an essential status especially since they are close to the apartments. The participants seem to enjoy a variety of supply offers that can be easily provided in a supply structure as is given in the Plano Piloto. What has changed is the presence of Hypermercados that are even bigger than the supermarkets in the Comércio Locais. These can usually attract people with lower prices, a wide range of offers and plenty of parking spaces. Over time, some new shopping centers have also been built in Plano Piloto and its border. Looking at the map of the tracking method and the questionnaires, it is obvious that people move further than only to their connecting Comércio Local to supply. The original plan for residents to walk to the adjoining Comércio Locais for supplies is therefore no longer being exercised.

Living in Plano Piloto

It has become clear that the Superquadras form the residential space in the Plano Piloto. They were thought of by

Lucio Costa as living quarters where functions are separated. Furthermore, everything should be available, from

medical care to schools, religious buildings, sporting facilities, everyday supply and space for leisure, such as

playgrounds. The ideal Superquadra should also have communal green spaces and should always have between eight and

eleven buildings. The urbanist and architect Prof. Sérgio Jatobá furthermore told us that another important aspect

was the separation from traffic. A Superquadra can only be entered and left by car from one street. This way only

residents enter the Superquadra and it is protected from transit traffic.

Figure 7 shows us how Costa imagined how the Superquadras should look like and how the separation of functions

looks on a spatial level. During our mappings and our visits of different Superquadras we could recognize all

these traits. But the condition of the buildings and facilities differed from one Superquadra to another. This

could be an indicator of the financial background of its residents or the success of communal efforts.

In order to learn more about everyday life in Plano Piloto we sat down with people who live there. Different

aspects were aborded during these discussions, such as the architecture of the buildings, the communal living or

the organization of the people living in Plano Piloto.

While visiting Bruno who lives in one of the first Superquadras in Asa Sul, we were able to have a look into

an apartment that had hardly changed since its construction. Bruno told us that many people changed the interior

design of their apartments and that only a few wanted to preserve the style of Oscar Niemeyer. From the outside,

everything corresponded to the initial plan. The building has two elevators for its residents and a service

elevator. Even if Brasília should eliminate the division between social classes, the residents used to have

housekeepers who lived with them and, for example, used these service elevators. Nowadays, these elevators are

used by construction workers. A resident, Gilney, who lives in a Superquadra in Asa Norte told us that people

still have housekeepers but that they no longer live with their employers but are commuting to Plano Piloto from

the satellite cities. This brings the lower classes together with the middle class because the housekeepers bring

their kids to Plano Piloto during the day and go to the same schools as the children of middle-class families.

Bruno, who has been living in Plano Piloto for a long time, told us that the residents from one building select

one spokesperson, whose task is to represent the building and its residents on an administrative basis. He named

examples like waste management systems that the residents wanted to implement. As for the visited Superquadra in

Asa Norte, the buildings didn't look alike; every building had a different facade. The buildings were built later

than the model Superquadra in Asa Sul, and no strict rules were applied concerning the looks. According to the

residents, Plano Piloto is mainly populated by the Brazilian middle class.

Nevertheless, we were told that up until recently, there was not a close neighbourhood community. However,

some residents were eager to change, throwing different projects like fruit trees accessible to all or a cofounded

playground for the children. Not all the residents participate in communal life. This division is often being

caused by different political beliefs which can sometimes lead to tension.

The apartment in Asa Norte was newly renovated, and the structure has been changed from its initial form. Here the

changes were more of a practical nature than an aesthetic. We could also observe differences in the state of

building by visiting different Superquadras and Comércio Locais. Some were in good shape, especially the original

Superquadras. Nevertheless, within a Superquadra, there were differences between the buildings and occasional

renovation works could be seen. The buildings in the Comércio Locais vary not only in their state but also in

their design. So are the buildings in the Comércio Locais of Asa Sul only one story tall and continuous all along

the street, with two to three passages. The Comércio Locais in Asa Norte are characterized by four to five, three

stories tall, buildings on every side of the road. These structures have basements, sometimes hosting businesses

or being used as storage. The buildings are accessible from all sides and are designed to maximize commercial

space. In some cases, the upper Stories were inhabited (people on the balcony or doorbells). These apartments are

known to be cheaper and often are inhabited by people who work in the businesses of the Comércio Local. Some

Superquadras have a large number of students living in them. Often residents sub-rent rooms and alter the interior

of the apartments in order to sub rent parts of them.

Every building in a Superquadra usually has security surveillance; some buildings even have a concierge. Other

remnants from the original Superquadra plans are the Bancas, or Kiosks and critical services, which can still be

found in every Superquadra. As we could see during our visits to different Superquadras, they differ regarding the

common areas and the spaces between the buildings. Some Superquadras are equipped with sporting facilities or

playgrounds while others don't have such spaces or they are in a desolate state.

According to Bruno, around 95% of the population of Plano Piloto have a car and use it in everyday life. The

emergence of the automobile as the primary way of mobility during the second half of the 20th century had a

consequence that the shops in the Comércio Locais faced the street and not as intended originally towards the

residential buildings. Finally we have to mention the characteristic pillars on which stand the different

buildings in the Superquadras.

Conclusion

Looking at how Plano Piloto residents supply themselves daily, it becomes clear that social and economic dynamics

influence commercial spaces and activities. Developments like the digitalization of our everyday life are

processes that could not have been included in the ideas of Costa and Niemeyer when they were thinking of how the

inhabitants would supply themselves. Offer and demand are ever-changing and so is society, and both influence each

other. The initially planned commercial spaces still exist today and are used as such, but they don't seem to

fulfill the needs. This is shown by the emergence of various shopping centers and bigger supermarkets. The

diversity within most Comércio Locais ensures that the inhabitants theoretically can meet their needs, such as

intended, but personal preferences are not considered.

As a consequence, residents visit other Comércio Locais or other commercial spaces within the Plano Piloto in

order to find what they want. This can be seen in the mental maps and in the tracking data. This observation leads

us to believe that the planners thought that supply habits could be planned or shaped in some way, not considering

the residents' individuality and their needs. It is essential to emphasize the dynamic character of such needs and

the interdependence of such with societal changes.

The preceding statements and the collected data don't legitimize general rulings but can point in a particular

direction. This lets us conclude that the idea of the Comércio Locais and their role as supply hubs for the

surrounding residents still exists today, but it failed to take into account the individuality of people and the

impact of a growing consumer society.

Moreover, the Plano Piloto failed to generate inclusive living space for all of Brazils social classes. The poor

live in the satellite cities as commute to the Plano Piloto to work. The Plano Piloto seems to be a stronghold of

the middle class. But even this class, that lives together in the Superquadras is divided by politics as Gilney

told us. Communal life is happening bottom up but fails to include all the residents and varies from Superquadra

to another.

In comparison with the satellite town of Águas Claras, where we can also see a heterogenous mix concerning shops

and supply possibilities, the biggest difference seems to be the residential buildings and their communal

organization. For more details concerning Águas Claras, click here.

Methods

The questionnaires were handed out to students of the UNB who live in Plano Piloto, such as to random pedestrians

we met while mapping the Comércio Locais. The total number of filled-out questionnaires is six, three men and

three women between the ages of 23 and 65. The questionnaire contained five open questions, one drawing section

for a mental map ending with some demographic questions about age, gender, living situation, number of people

living in the same apartment and if they are working and/or studying.

This method could provide an overview of different opinions and practices. With only six people answering in

total, we cannot take any conclusions for general habits out of the results. In order to still use the filled-out

questionnaires, all answers were collected and sorted into a table that provides an overview of different habits

concerning each topic of the questions asked. The mental maps were analyzed and compared.

The trackings were practiced by four people living in Plano Piloto. Three males and one female between 23 and 35 years old. They were given an account for an app called Strava. With this app, people usually track their sporting activities (e.g., running: route, distance, speed, elevation, heart rate). For this study, the focus was only on the route they covered. After setting up their smartphone with the Strava app and given account, they started a tracking activity on Strava but continued their everyday life just as they would without tracking. The tracking was active for four days with breaks at night. The participants could also stop and start the tracking at any time and any place if they wanted to. These trackings resulted in exportable routes about the movement of the tracked people. Like this, it's possible to see if they go to the same Comércio Local every day, to different ones around their Superquadra and further away, if they leave Plano Piloto if they stop at a supermarket while on their way from A to B, etc. Figure 6 shows the different tracks of the four participants during their four days of tracking.

In human geography, mapping is seen as a special form of observation. With their help, spatial surveys can be created (Mattissek et al. 2013). Mapping aims to generate spatial location combined with specific characteristics using primary data for a delimited unit (Fülling et al. 2021). A total of 12 Superquadras were selected for our Mapping. Considering that four Superquadras results in one Unidade de Vizinhança, a total of three Unidade de Vizinhança were examined, including both the housing units and the Comércio Locais within and adjacent to them. A mapping key was prepared in advance. This is divided into the following sections: gastronomy, food specialized retail, supermarket, body services, drugstore, other services, clothing, other retail, doctors, pets and vacancy. During data collection, the position, area, exact name, details and price range were noted in each case. In the analysis, the individual results of the respective Comércio Locais and Unidade de Vizinhança were then quantified to determine which sectors predominated.

As a fourth method, we must name the interviews that we had with two residents from Plano Piloto. Bruno and Gilney live in Asa Sul, respectively, in Asa Norte and each one of them invited us to their Superquadra to discuss life in Plano Piloto. These visits and discussions happened in an explorative manner. We tried to understand everyday life in the different Superquadras of Brasília.

All illustrations, graphics, tables and photos used in connection with the topic Daily Life: Plano Piloto as well as the present text were

created or taken by Ayyoub Benkhaddou, Marco Wegler and Sarah Rasi.

References

Fülling, J.; Hering, L.; Kulke, E. (2021): Kartierung und Foto-Dokumentation: Vorschlag für ein raumsensibles Mixed-Methods-Design am Beispiel einer Einzelhandelskartierung. In: Heinrich, A. J.; Marguin, S.; Million, A. (Hrsg.) (2021): Handbuch qualitative und visuelle Methoden der Raumforschung. transcript Verlag. Bielefeld. S. 345-363.

Madaleno, I. M. (1996): Brasília: the frontier capital. In: Cities 13 (4). S. 273-280.

Mattissek, A.; Pfaffenbach, C.; Reuber, P. (2013): Methoden der empirischen Humangeographie. Das geographische Seminar. Westermann. Braunschweig.

Popp, M. (2020): Wer kauft wo? Die Einkaufsstättenwahl der Konsumenten. In: Neiberger, C.; Hahn, B. (Hrsg.): Geographische Handelsforschung. Springer Spektrum. Berlin. S. 75-87.

Tattara, M. (2011): Brasília's Superquadra: Prototypical Design and the Project of the City. In: Archit Design 81 (1). S. 46-55.