Research question and topic

What forms of space appropriation are visible in the Plano Piloto and in what way can the construct of

planned, produced space create urbanity?

How is space appropriation and urbanity happening in selected

places?

These questions arose when the research about Brasília and its core, the Plano Piloto, started. One of the first

difficulties encountered during the research process was the eurocentric perspective held by the student

researchers regarding the construct of a ‘city’. This had to constantly be kept in mind, since it would otherwise

have compromised a neutral research process.

Theory

The concept of urbanity is diverse and hard to define; a definition based solely on the size of a city (number of

citizens & footprint) is not enough (Wirth 2020). Urbanity can be translated as a cognitive construct; the

collective identity of a place and lifestyles that evolve from it, regardless of whether a city is defined by

administrative standards, or it being just a rural community.

Given this context, the city of Brasília stands out as it is a planned city, the new capital of a rising state,

and a promise to society of better days to come (Stierli 2013). However, the Brasília of today struggles with

uncontrolled growth and spatial segregation, which makes it almost impossible to live a life without a car due to

the planning being based on the separation of social functions (Bezerra et al. 2017). The aspiration to build a

modern capital with new forms of community living and social integration failed, as nowadays many citizens live in

satellite cities up to 50 km away from the city centre, the so-called Plano Piloto (Cafrune 2016). In

contrast to the city development of Brasília, Brazil was one of the first countries to legitimate the Right to the

City in a national law, the Estatuto da Cidade (Mengay and Pricelius 2011), which was issued to stand

against spatial and social segregation.

The urban aspect of a collective identity of a place stands out in Brasília, not only within Brazil, but globally.

People came from all over the country to settle in this new city in the middle of the cerrado, a dry

plateau in

the backcountry, with almost no pre-existing infrastructure. It was designed by Oscar Niemeyer as a symbol of

modern times, to show the evolving modern Brazilian society. Now, two generations later, one might expect to

encounter a version of Brasília as a thriving and inspiring capital, much more than just the administrative heart

of a huge country. However, old metropolitan centres like São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro still define the typical

charisma of the Brazilian city. This does not mean it does not exist in Brasília, but one has to look more

closely, and to always keep in mind the history of Brasília and how society there has formed since the

independence of Brazil (see About

Brasília).

Results and interpretation with theoretical reference

The architect Oscar Niemeyer and Lúcio Costa, the urban planner behind the construction of Brasília wanted to

build an icon of modernity to manifest the evolving Brazilian society of the modern era. The planning of Brasília

was based on the separation of social functions, which at the time was considered to be the most modern way of

living. The modern society - as Niemeyer perceived it - was based on access to modern technology, which at that

time meant to be able to use automobiles without limitation (see About Brasília). The segregation of the

Brazilian

society of today is based on the limited access to functions because of limited means, which can be seen in the

use of public transport by lower income groups and the domination of the informal sector in the Rodoviária

(central bus / metro station) in contrast to the Conjunto Nacional (shopping mall) (see Mobility in Brasília). With the change of global

societies through increased environmental awareness and the breakup

of social norms and values all over the world, Brasília seems like a remnant of the modern times of acceleration

(Williams 2007). The transition to the postmodern era needs yet to be implemented but is bound by the planning of

Niemeyer/Costa. One could say that Brasília as an icon of modernity does not serve the already existing postmodern

society of contemporary Brazil anymore and only fortifies the growing segregation within its society (Kaiser 1987,

Wehrhahn 1998, Struck 2017).

Due to the decentralization of the city by the separation of functions, it is difficult to identify an actual core

of the city within the Plano Piloto. During the research progress, it was decided to envisage the core of

Brasília

to be the tricentre, consisting of the Rodoviária, the Edifício Conic (a cultural, shopping and service

centre)

and the Conjunto Nacional, and to subsequently compare this tricentre with the Vila Planalto neighbourhood. The

following results are based on the interpreted findings resulting from the application of several different

methods used in the fieldwork.

Making urbanity comprehensible is not easy. The concept of the city within the city according to Ungers and

Kolhaas (1977) - describes a polycentric form of organisation, an ‘archipelago‘ of differences so to speak, which

favours urbanity. According to this understanding, today's cities cannot be understood as a whole, but as a

complex structure with many different ‘islands’ which all have different characters. Urbanity thus meets in

condensed form in the ‘islands’. If we apply this concept to Brasília, we can identify various such ‘islands’.

Firstly, the area around the Rodoviária, the Edifício Conic, and the Conjunto Nacional can be identified as a

special place for urbanity. In addition, the Vila Planalto neighbourhood is of great relevance considering its

history as a former residential area of construction workers. It is known as one of the most diverse

neighbourhoods in Brasília. This refers to the income differences, the diversity of the residents, as well as that

of the architecture. Urbanity is often associated with diversity, so Vila Planalto is an appealing

neighbourhood

for research. Through the method of strollology/walking (see methods chapter), this

impression was consolidated.

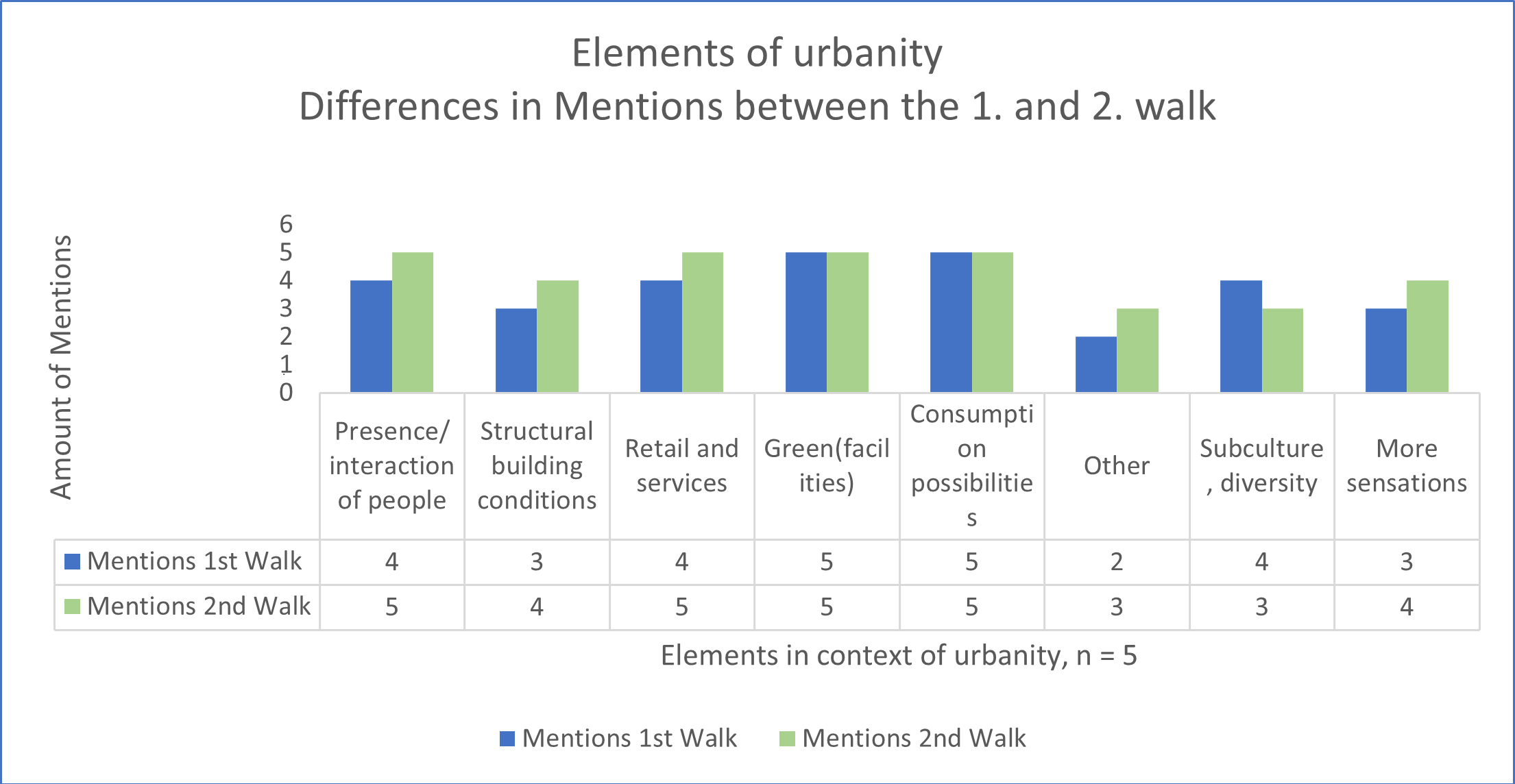

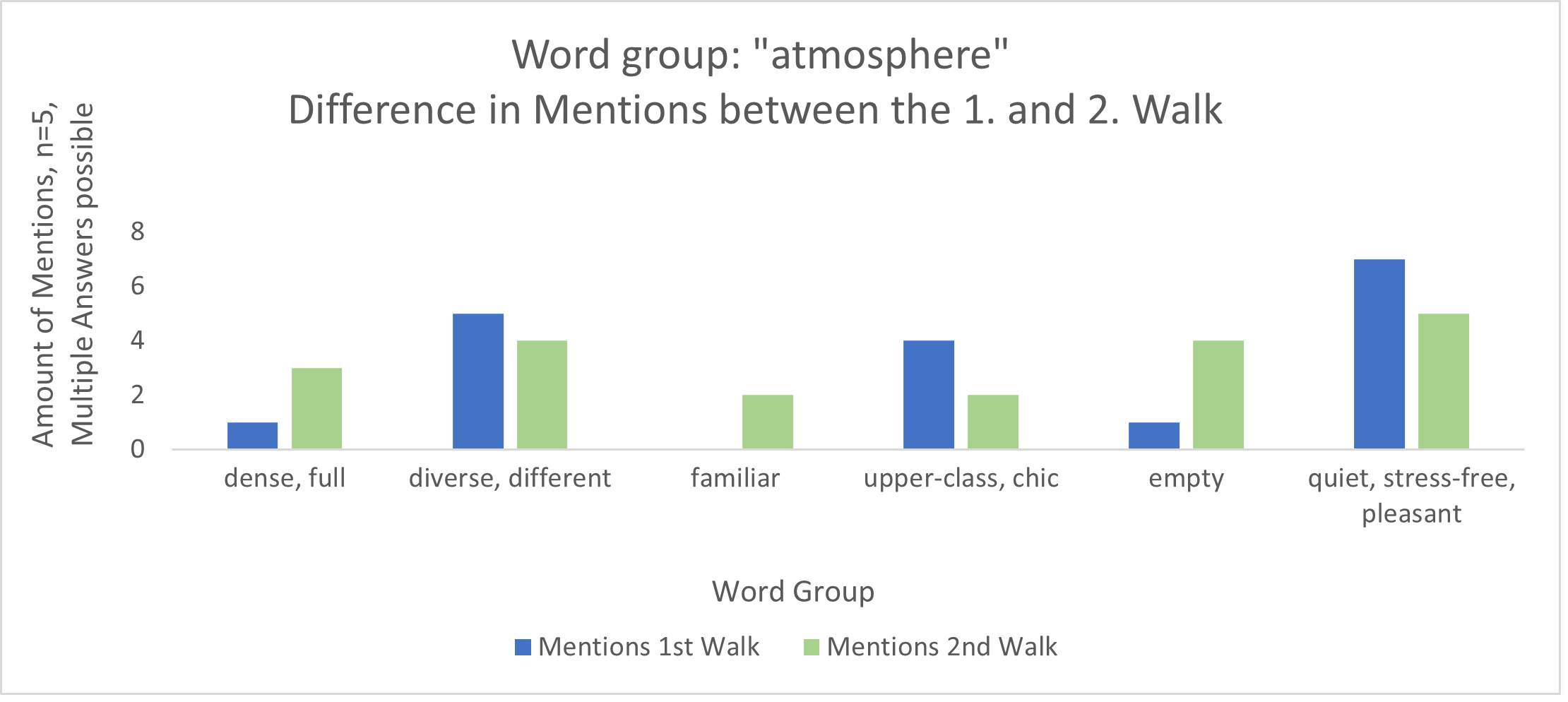

Important aspects of urbanity are human presence and interaction, green spaces and consumption opportunities, as

well as the influence and diversity of subcultures (see diagram). Attributes that were mentioned during the

fieldwork in connection with urbanity were ‘dense/full‘ or ‘diverse/different‘. At the same time, however, Vila

Planalto was also described as ‘familiar, upper-class, and chic‘ as well as ‘quiet, stress-free, and pleasant‘

(see diagram). This discrepancy shows how different the perceptions of the neighbourhood are. In the map, some

photos which were taken during the walks are shown and explained in a wider context.

In summary, Vila Planalto is one of the rare places where the inhabitants successfully fought the planning by the

government. Within the ‘island’ of Vila Planalto, individualism, participation, space appropriation, and

subculture are quite visible, which indicates a vivid urban life. Although different perceptions such as emptiness

or ‘chicness’ underline the diversity and complexity of the area. In contrast to other ‘islands’ in Brasília, Vila

Planalto more closely follows the Western image of a neighbourhood as well as the understanding of urbanity

including different architectural structures, restaurants, and life in public spaces. One could argue that it is

the counterweight to the strictly planned area of the Plano Piloto, which is also geographically very close to all

central functions.

Within the context of urbanity, keywords such as ‘dense’ and ‘anonymous’ are some of the main aspects of urban

living. The Rodoviária (methods: observation and mapping) might seem as a place of

futile exchanges between

people, but it does serve as a regular meeting point not only for mobility, but also consumption, since the

informal sector is quite dominant here. The informal sector is tolerated, even though the authorities are present;

it almost seems as if there is a symbiotic co-existence. Moreover, knowing that the car is the dominant means of

transport in Brasília amongst members of the upper socioeconomic class, it can be concluded that this space is

predominantly frequented by people from lower income groups (Holanda 2022).

The Edifício Conic (methods: interview, mapping, walks) was once a place where

urbanity was shaped by

strolling. Until the late 1980s, it was home to several small theatres, restaurants, pubs, cafés, etc. According

to Lúcio Costa, it was designed to have a sort of “Mediterranean atmosphere” where the public could spend evenings

as a community. However, due to lack of financial investment, the sense of place changed, with sex work settling

in vacant spaces. Today, restaurants or snack shops and a bar are visible in a few places. Otherwise, the place is

dominated by vacancy, retail, party offices, churches, and private clinics. In addition, events such as concerts

take place from time to time (Rossi 2022). However, the Edifício Conic and its surroundings present a security

risk, especially in the evenings, which is in contrast with the semi-public Conjunto National which is guarded by

security guards, and subject to strict opening hours. The Edifício Conic and its surroundings stand out in the

tricentre because of its subcultural character, which can be seen in the numerous graffities and murals.

The third point of the core, the Conjunto Nacional (methods: walks), may be the most inviting place

to stroll around for the following reasons: As a shopping centre it seems primarily to be a place of consumption,

however, the compulsion to buy does not exist and furthermore, it is a secure and climatized place through which

one can stroll, meet friends, or spend a lunch break. Technically it is not a public space, since there are rules

and security, but in a segregated country like Brazil this could be a factor for the appeal of secured,

semi-public places like the Conjunto Nacional. The combination of security, air-conditioning, visual diversity of

the shops, and the restaurant level give people the opportunity to spend a whole day as a leisure activity

(Rückert 2002). Compared to the Rodoviária, the informal sector is completely absent in the Conjunto Nacional,

which leads to the conclusion that it is used on average by higher-income groups. However, this would have to be

the subject of further investigations.

The colliding and coexisting of different ways of living make Brasília special in its own way. Urbanity almost

seems raw, like something that already put down roots, but got overtaken by the rapid evolution of society and the

new standards and needs of a modern city life. Thus, it struggles to grow and blossom. In conclusion, urbanity can

be perceived in the different locations of the tricentre as well as in Vila Planalto. As a construct that

distinguishes the urban from the rural, it is produced by the inhabitants of Brasília. Compared to European cities

such as Amsterdam (see the Lévy model (2020)), urbanity is less related to a concrete centre and occurs

selectively. Different groups of people and incomes create diverse forms and expressions of urbanity in various

places (Salin 2020), some of which exist side-by-side, but separately from each other as ‘islands’. In some

places, political activism is a sign of urbanity (Salin 2020), while urbanity can also be recognisable in the form

of (e.g. political) graffiti. Looking at each of these places in isolation, the time of day is an equally

influential factor. At the Rodoviária, the informal sector creates liveliness at daytime, while at the Edifício

Conic, a bar creates urbanity at night - especially on weekends. Vila Planalto is highly frequented during

lunchtime. Other places where urbanity can be perceived in Brasília are the Comércios Locais – local centres of

the respective super quadras (see Plano Piloto:

Daily Life) , or green spaces such as the Parque da Cidade – the

city park of Brasília (see Leisure & Open

Space).

Methods and limitations of the methods

In order to approach the question of spatial perception and use in regard to urbanity, a 'strollology

method' was

used: specifically, the 'continuous stop walking method' based on Schultz and van Etteger (2017). Strolls were

conducted in the area of Vila Planalto (see route on

map). This area was chosen because of its relevance to

urbanity, which was highlighted in the literature and in interviews with experts. The method was carried out on

25.04.2022 with five students. The first walk (from 10 a.m.) was carried out continuously and documented by

writing down impressions and experiences afterwards. Then (from 12 p.m.), the same route was walked again. This

time however, breaks were taken at regular intervals to let the surroundings take effect and to facilitate the

documentation of the experience via photos and notes. These data were then evaluated with qualitative analyses,

visualised, and summarised. Some of them are shown on the

map and in the diagrams above. The difficulty within

this method was the framing such as the time of day or weather conditions, and also the Eurocentric view on

urbanity of the European students, and the limitations stemming from individual concentration spans. Therefore,

the role of subjectivity must be kept in mind, even though guiding questions were given to mitigate this aspect.

For further research, walks on different days and times as well as more non-European participants are recommended,

in order to expand the data.

The results for the tricentre are based on a mix of methods consisting of observations at the Rodoviária,

mapping

of the ground floor level of the Rodoviária as well as the ground floor level of the Edifício Conic, and an

interview with Taína Rossi about the significance of the Edifício Conic. In addition, walks took place in both the

Edifício Conic and the Conjunto Nacional to gather further impressions.

At the Rodoviária, a total of four covert, non-participatory observations (Thierbach and Petschick 2014)

were made

on two days (Saturday, 23.04.22 and Tuesday, 26.04.22) in the morning (from 10 a.m.) and afternoon (from 1:30

p.m.) for 60 minutes each. They were carried out by four people observing each time. For this, the students had an

observation sheet with set categories. Some of the criteria are: characteristics of people, subcultural

expression, appropriation of space, interaction. Supporting videos (on saturday at the section D; on tuesday at

the section B) were taken showing the frequency of visitors (difference between morning and afternoon) as well as

the presence of the informal sector.

Videos

All illustrations, graphics, tables and photos used in connection with the topic Urbanity: Urban Living as well as the present text were created or taken by Charlotte Poppa, Katharina Krebs and Marlene Benzinger.

References

Cafrune, Marcelo Eibs: Das Recht auf Stadt in Brasilien. Genese, Anspruch und Wirklichkeit des Rechts. In: Kritische Justiz 49 (1), pp. 47–60. DOI: 10.5771/0023-4834-2016-1-47.

Crease, David (1962): Progress in Brasilia. In: Ekistics 14 (83), pp. 139-143.

Holanda, Frederico de (2022): Brasília: cidade moderna, cidade eterna. 18.04.2022, Brasília. Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade de Brasília.

Kaiser, Wilfried (1987): Städtische Entwicklung und räumlich-soziale Segregation im Bundesstaat von Brasília (Distrito Federal). In: Tübinger Geographische Studien 93, pp. 175–197.

Koolhaas, Rem; Ungers, Oswald (1977): The city in the city, Berlin: A Green Archipelago. Berlin: Manifesto.

Lévy, Jacques (2020): Urbanitätsmodell. In: Dirksmeier, Peter; Stock, Mathis (Hg.): Urbanität. Basistexte. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, pp. 167–177.

Mengay, Adrian; Pricelius, Maike (2011): Das umkämpfte Recht auf Stadt in Brasilien. Die institutionalisierte Form der "Stadt Statute" und die Praxis der urbanen Wohnungslosenbewegung des MTST. In: Holm, Andrej; Gebhardt, Dirk (Hg.): Initiativen für ein Recht auf Stadt. pp. 245-270.

Olbrich, Gerold; Quick, Michael; Schweikart, Jürgen (2002): Desktop Mapping. Grundlagen und Praxis in Kartographie und GIS. 3. Aufl. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag GmbH.

Rossi, Taína (2022): The change in the meaning of the Edifício Conic. Mini-interview, 28.04.2022, Brasília.

Rückert, Ira (2002): Zur kulturraumspezifischen Funktionalität von Betriebsformensystemen des Einzelhandels, dargestellt am Beispiel ausgewählter Shopping-Center in Sao Paulo. Retail and Consumer Culture. The cultural and space related functionality of retail systems: The case of selected Shopping-Centres in Sao Paulo. Dissertation zur Erlangung des wirtschaftswissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades des Fachbereichs Wirtschaftswissenschaften der Universität Göttingen.

Salin, Edgar (2020): Urbanität. In: Dirksmeier, Peter; Stock, Mathis (Hg.): Urbanität. Basistexte. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, pp. 75–95.

Schultz, Henrik; van Etteger, Rudi (2017): Walking. In: Brink, Adriden van; Bruns, Diedrich; Tobi, Hilde; Bell, Simon (Hg.): Research in landscape architecture. Methods and methodology. London, New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 179–194.

Stierli, Martino (2013) Building No Place. In: Journal of Architectural Education 67 (1), pp. 8-16, DOI:10.1080/10464883.2013.769840

Struck, Ernst (2017): Brasília: eine Utopie als Repräsentation einer Supermacht. Von der Vision einer Stadt zum musealen Relikt. In: Anhuf, Dieter (Hg.): Brasilien - Herausforderungen der neuen Supermacht des Südens. Mit 58 Farbabbildungen, 86 Farbbildern und 7 Tabellen. Passau: Selbstverlag Fach Geographie der Universität Passau (Passauer Kontaktstudium Geographie, 14), pp. 23–33.

Thierbach, Cornelia; Petschick, Grit (2014): Beobachtung. In: Baur, Nina; Blasius, Jörg (Hg.): Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien, pp. 855–867.

Werhahn, Rainer (1998): Urbanisierung und Stadtentwicklung in Brasilien. Aktuelle Prozesse und Probleme. In: Geographische Rundschau 50 (11), pp. 656–663

Williams, Richard (2007). Brasília after Brasília. In: Progress in Planning 67, pp. 301–366. DOI: 10.1016/j.progress.2007.03.008.

Wirth, Louis (2020): Urbanität als Lebensweise. In: Dirksmeier, Peter; Stock, Mathis (Hg.): Urbanität. Basistexte. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, pp. 45–65.

Web sources:

https://issuu.com/eduardaaun/docs/caderno_o_avesso_do_avesso_eduarda_ (15.08.2022).

https://issuu.com/eduardaaun/docs/guia_de_bolso (15.08.2022).

https://jornaldebrasilia.com.br/entretenimento/eventos/abram-alas-para-o-carnaval-do-conic-mais-de-40-atracoes-em-seis-dias-de-festa/ (15.02.2022).

https://www.metropoles.com/conceicao-freitas/conic-um-labirinto-de-cultura-jovem-no-centro-urbano-de-brasilia (15.08.2022).