When Lúcio Costa realised his vision of Brazil's new capital, the architectural guiding principles were primarily of western-modern origin. These principles eventually led to the creation of more and more satellite cities around Brasília in the following decades, to compensate for the lack of infrastructure and housing options available to the ever-growing population of the Federal District of Brasília. Águas Claras is one of the youngest administrative regions and was designed in the 1990s by architect and urban planner Paulo Zimbres, with the aim of meeting the still steadily growing demand for living space. The aim was to create more living space on less land area by means of building high-rise complexes (Sampaio Silva 2016). Águas Claras is currently one of the fastest growing urban areas in the Federal District and has been an independent administrative region since 2003 (Costa & Lee 2019), yet several questions arise when considering its development and role within Brasilia: How does Águas Claras, which was planned in the 1990s, differ from the Plano Piloto in terms of living, medical care and everyday supply? Is the period in which a planned city is created decisive to the development of supply structures? How were the residents of Águas Claras able to leave their mark on the space?

Living

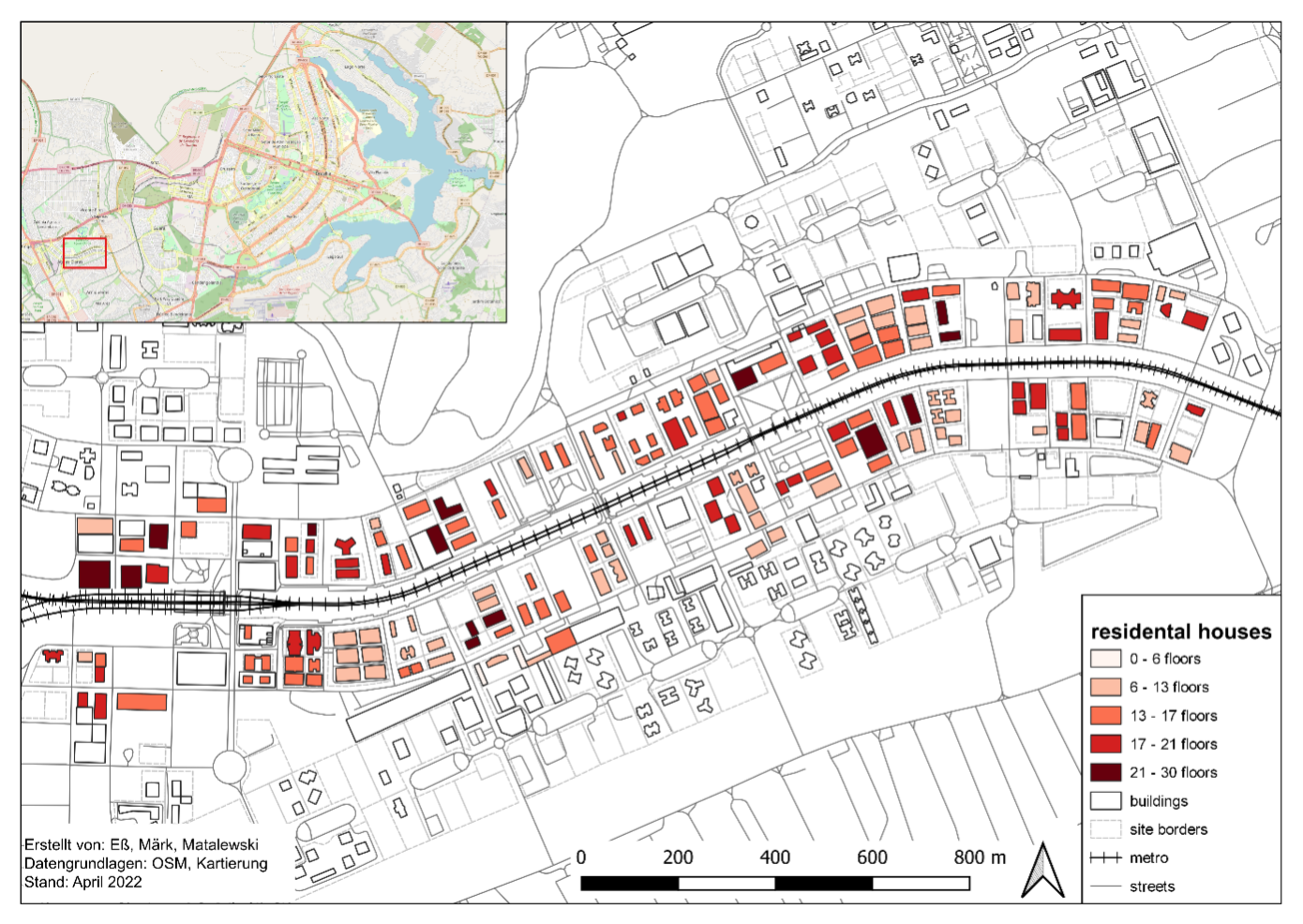

To understand how the living situation in Águas Claras can be explained, it must first be understood that the planning of Águas Claras was based on a linear city model. This model is characterised by the fact that the settlement in question is built along a straight line provided by transportation infrastructure (in the case of Águas Claras, the metro). This results in an almost unlimited expansion of the settlement space or urban development along a linear path, as well as a close connection between urban and natural spaces (such as the Parque Ecológico de Águas Claras) in the direction tangential to the main infrastructural axis (Heineberg 2001; Kainrath 1997; Sauer & Rosner 2011). Mapping of a predefined area (fig. 1) shows that Águas Claras presents itself as a highly condensed and verticalized city. The lowest buildings are six storeys high. On average, most buildings have between eleven and twenty floors and the tallest building has 30 floors. It seems that there is no clear concentration of particularly high or low residential buildings; rather, the number of floors seems to be left to the discretion of the architects and builders. However, this was also favoured by the fact that at that time the demand for appropriate living for the middle class of the population had increased considerably, as Fernando Luiz Araújo Sobrinho (professor of geography at the UNB) explained. The phenomenon of living densification through verticalization in the form of high-rise buildings reflects the concept of sustainable urban development (Heineberg 2011). The majority of the living complexes are separated from public areas via walls, video surveillance, and doormen. This practise can be explained by the concept of spatialisation of (in)security and space-oriented security policies. These security strategies led to the creation of vertical gated communities (condomínios fechados verticais) for the middle class, so that only condomínio-paying residents have access to the apartment buildings and their communal amenities (Coy & Pöhler 2002; Glasze 2011). A survey of residents of Águas Claras as well as interviews with experts revealed the housing situation inside the apartment buildings: the value of the rental price of the flat increases with the verticality. That means that flats on the upper floors of a building, which may have the same floor plan as the flats on the lowest floors, cost significantly more. The primary reasons for this are the noise from the streets on the lower floors, and the cooler temperatures, better lighting and better view on the upper floors. According to Fernando Luiz Araújo Sobrinho, on the upper levels there are also often large apartments spanning across two or three floors. Almost 75% of the respondents stated that they own their own apartments; the others live in rented flats. This figure is an indication that mainly people of the middle class live in Águas Claras. Respondents reported having between one and seven rooms in their home, with the mean value being around three rooms, and the median footprint of the apartments being 82m². The size of the flat generally increases with the number of people in the household, with the number of children playing an especially large role. From the information provided by the survey it can also be concluded that partner households predominate. If there are children living in the household, there is mostly only one child.

Supply Structures

In contrast to the Plano Piloto, the concept of functionalism was not applied in Águas Claras. In fact, the problems associated with the earlier functionalist model gave rise to a guiding principle of sustainable urban development and thus to more environmentally compatible urban planning. This principle focuses on urban densification and on a functional mix, thus creating a so-called city of short distances (Heineberg 2001, Heineberg 2011, Saurer & Rosner 2011). Via mapping, surveys and interviews, it was investigated how this functional mix is reflected in the existing supply structures, and to what extent the residents make use of these amenities. Sub-aspects of these investigations are gastronomic supply (bars, restaurants, cafés and street food stalls), food and everyday supply (shopping centres, supermarkets, weekly markets and specialised food stores) and other supply (real estate companies, medical services and other services) (Glückler 2011). From the results of the mapping, density distribution maps of the sub-aspects were created in order to find out which supply structures are available to residents. When it comes to accessing supply facilities, a distinction is made between three categories: motorised individual transport (car, moped motorbike etc.), non-motorised individual transport (bicycle or walking) and public transport, which is also referred to as modal split (Kagermeier 2011). The results of the survey show how these existing supply strategies are used and which means of transport were chosen.

Everyday Supply

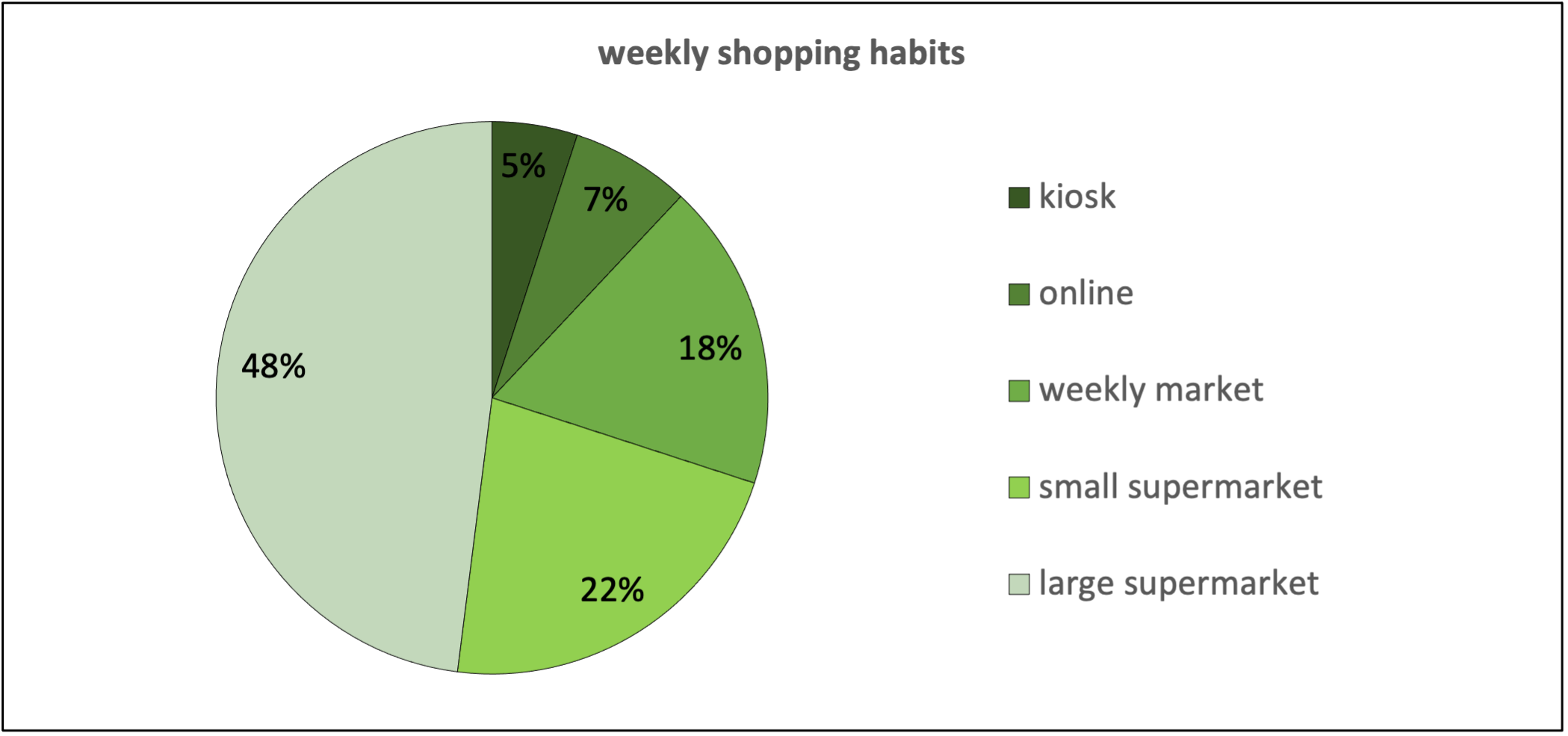

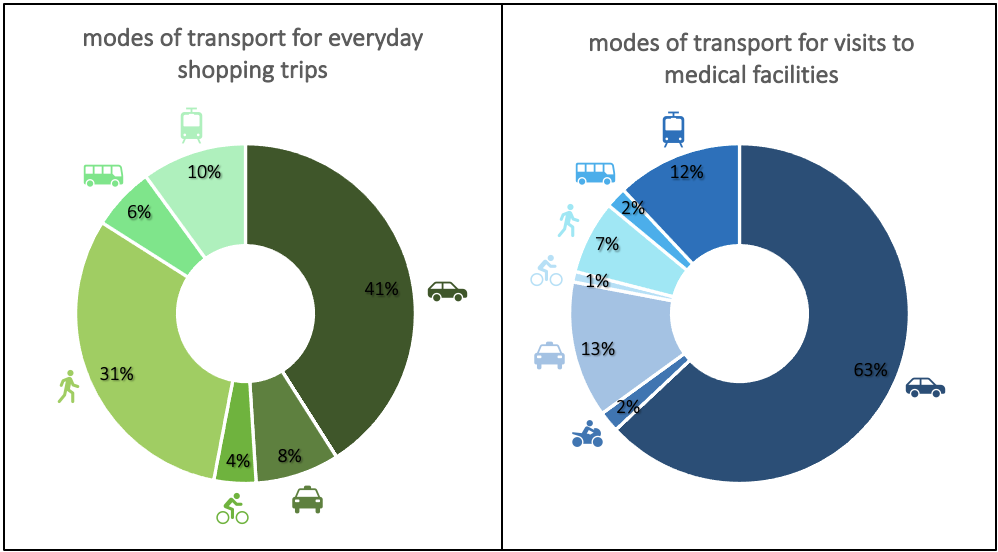

On average, the participants of the survey eat outside their homes (restaurants, cafés etc.) two to three times a week, and the rest of the time they provide for themselves at home, which means that they regularly visit supply facilities of everyday goods. 48% do their everyday shopping in larger supermarkets, but 22% also use smaller supermarkets (fig. 2).Kiosks, weekly markets, or online shopping is used less. According to the survey, shopping centres are of no importance for everyday supplies. The majority of respondents shop for their everyday goods one to three times a week, and just under one fifth even go shopping less than once a week. On average, respondents take about 5 to 15 minutes, but often 15-30 minutes, to get to supermarkets. Almost half use a car to do this, about 31% walk, and about 16% use public transport (fig. 3, left). Thus, most walk or use their car to do their shopping. The results of the survey show that in terms of everyday supply, almost half of the participants use a car and the majority go shopping one to three times a week, mainly making medium to large purchases which cannot easily be transported via other means of transport. The fact that the respondents take an average of about 5 to 15 minutes to get to everyday supply facilities may also be related to the use of cars and to the even distribution of the supply facilities within the administrative region.

Medical Care

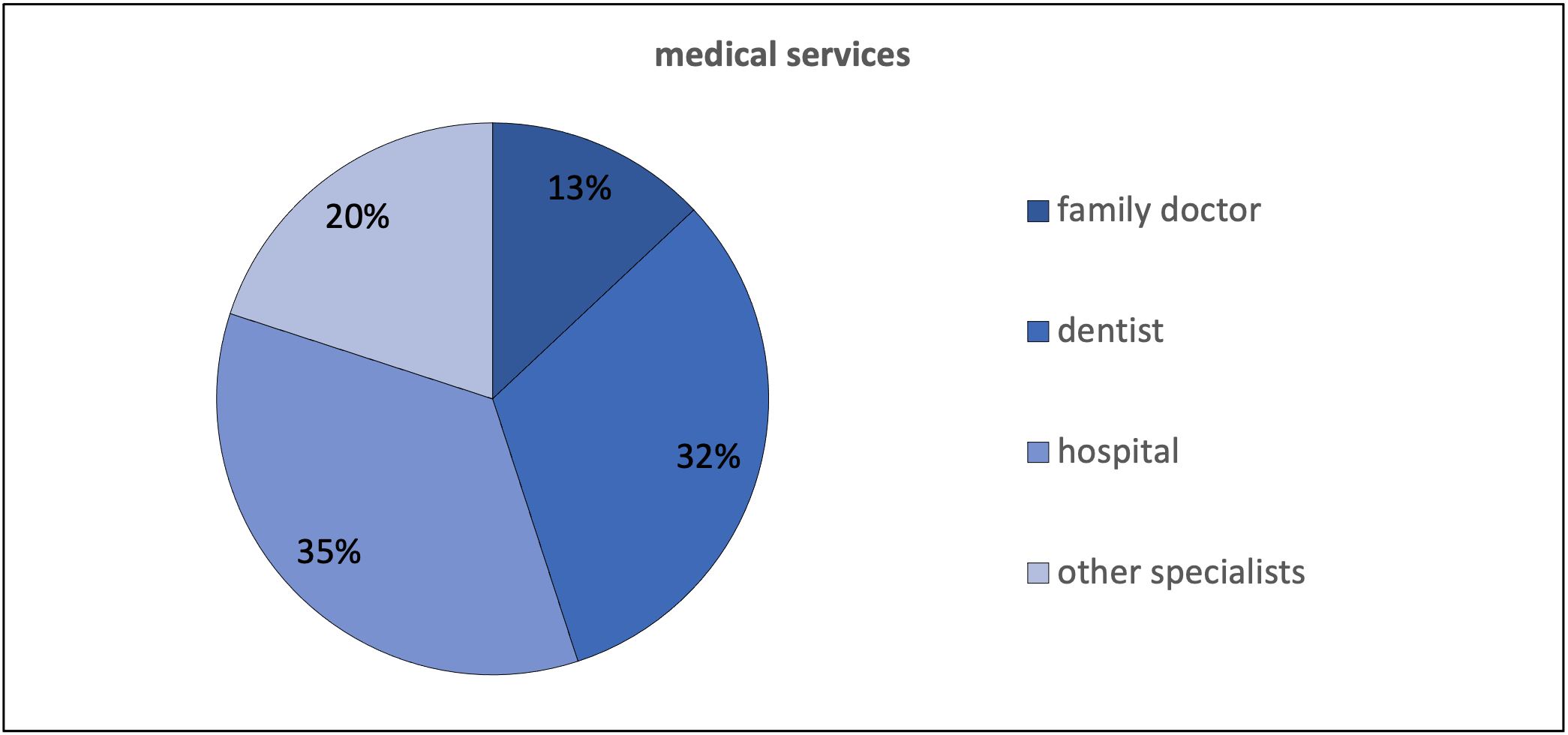

Regarding medical care, it can be said that the vast majority of the participants are privately insured, with very few using the public health system SUS (Sistema Único de Saúde or Public Heath System). Only a few visit a family doctor; most go to the hospital. Specialists such as dentists are visited regularly (fig. 4). How often medical facilities are visited is not related to age or employment status. Rather, educational attainment plays a role, because the higher the educational attainment, the more likely it is that people have private insurance and thus the more frequently they visit medical facilities. 63% of the respondents use a car to get to medical facilities (fig. 3, right). Around 14% use public transport, such as bus or metro. Non-motorised private transport is hardly represented: only 7% go on foot and only 1% by bicycle. This is likely explained by their health condition. Most of the participants need on average 15-30 minutes to get to medical facilities. Very few state that they need less than 5 minutes or more than 30 minutes. However, for public medical services, residents have to leave Águas Claras and travel further afield due to the lack of public infrastructure within the administrative region.

Everyday life in Águas Claras compared to Plano Piloto

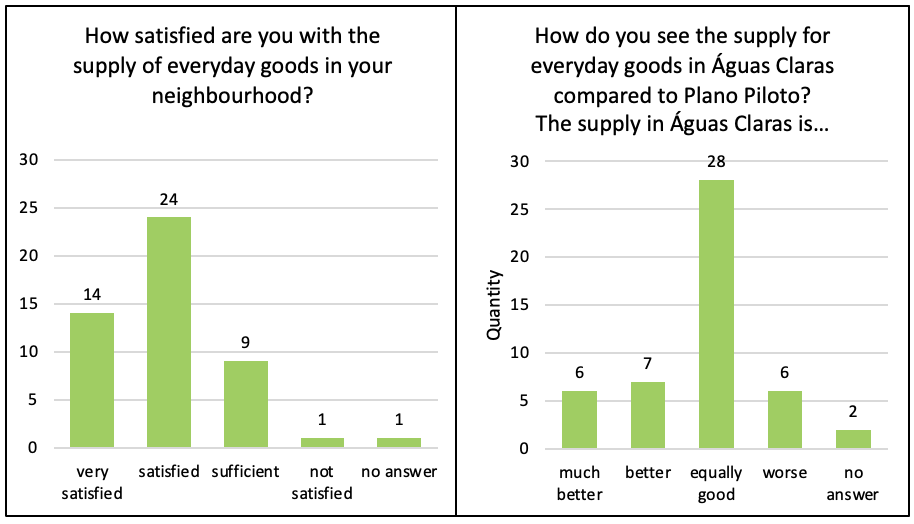

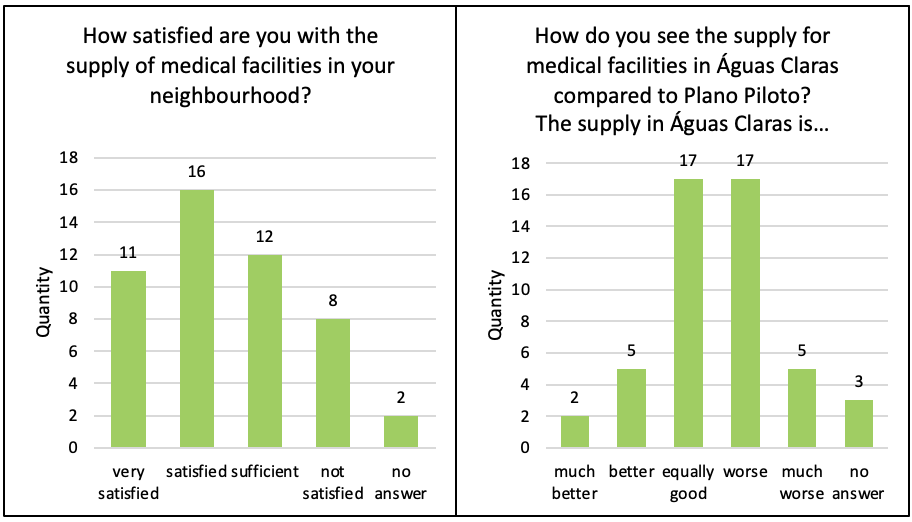

Respondents of the survey were asked how satisfied they are with the existing supply and how they rate it compared to Plano Piloto.

Everyday Supply

Regarding to the everyday supply in Águas Claras, the residents are generally satisfied with what is available (fig. 5), which is also reflected in the answers to the survey question regarding a possible need for improvement: "[...] I don't think there are any problems in relation to commerce and services in Águas Claras". Compared to the offerings in the Plano Piloto, they mainly rate Águas Claras as equally good, 26% of the respondents would even describe it as (much) better. How satisfied people are with the offerings is not related to age or educational attainment, but there is a tendency for women to be generally more satisfied than men. It has also been shown that the higher the educational qualification of the participant, the less satisfied the person is compared to the Plano Piloto.

Medical Care

Respondents are less satisfied with the provision of medical care than they are with the provision of everyday care: a quarter of respondents find the medical facilities just adequate, and 16% are not satisfied with the provision (fig. 6). This satisfaction picture is also reflected in the following statements of the respondents: "[...] We need a good public hospital" or "Here in Águas Claras we need a public hospital and also a health centre. The people who live here have to go to Taguatinga or Guará". It seems that people with private health insurance in Águas Claras are adequately covered and that there are enough private hospitals and health centres. However, people insured through the public health system (SUS) are less satisfied with the provision of medical care. When asked about the medical services in Águas Claras compared to the Plano Piloto, 35% of people said they find them to be equal and also 35% would describe them as worse. How satisfied respondents are with the medical facilities is not related to age or highest level of education, but satisfaction is related to primary employment status - and therefore potentially to the insurance system - as well as to age. Men tend to consider the medical facilities adequate, while women rate them to be worse in Águas Claras, when compared to the Plano Piloto.

Methods

Mapping

In general, a map is an overview of objects, their location, their spatial context, and their distribution patterns. As a further consequence, the representation within digital geographic information systems (GIS) serves the purpose that maps can be designed interactively and dynamically and combinations with photos, videos, analytical representations etc. are possible (Saurer & Rosner 2011). In this research project, spatial information from Águas Claras was collected, processed, evaluated and mapped. For the mapping, an approximately 2.5 km long section along the metro line of the linear city was divided into three sub-areas of roughly equal size, in which all buildings and shops were mapped analogously according to their use or function. Although such partial mapping may help to shed light on the use of the buildings within this mapping area, it cannot be used to draw conclusions about the entire satellite city as a whole. The basis for the map was a topographic map, in which basic elements like building outlines, the street network, and the mapping boundaries were drawn in advance. A mapping key was made in advance, which included numerous aspects of living, everyday life and medical care, with the added possibility of making new categories if necessary. The spatial reference is thus limited to quantitative local discreta. In addition, the number of storeys was noted for the residential buildings and the price ranges of restaurants were also rated subjectively. In the next step, the mapping key was generalised to better reflect the research questions, a legend was adapted, and the analogue mapping was digitised in QGIS 3.24. From the information obtained, it was then possible to generate several thematic maps that provide information about building use and also about the spatial distribution within the administrative region. This corresponds to an object-related, problem-oriented approach. OpenStreetMap Shapefiles „roads“, „residental“, „buildings“ and „railways“, which are free to use, were utilized for improved visual representation of the maps.

Survey

Survey types include the classic methods (in person, via telephone, and written correspondence), but also online surveys, which are considered a special form of written survey. In general, surveys are used to gather facts, opinions, knowledge, attitudes, or evaluations of people using standardised questions that can be either open or closed. The online survey is characterised above all by its time and cost-efficiency compared to classic survey methods. Further advantages are the high response rate and the easy sharing via e.g. social media (Batinic 2003; Meier Kruker & Rauh 2005). The surveys in this research project were completed in both analogue, written form in Águas Claras, and through the internet via the online survey tool LimeSurvey. Since the questions were identical, the answers from the analogue surveys were then combined with those from the online survey. This facilitated the subsequent evaluation. After cleaning the data of outliers and incomplete responses, the remaining 49 data sets were recoded into a numerical format and analysed in SPSS. This enabled descriptive statistics, frequencies, and correlations to be determined. The open-ended questions were evaluated qualitatively and used to substantiate the statements.

Mobile photo observation

Mobile photo observations are non-intrusive, non-participatory observations in which the behaviour of people was observed within the context of a given space (Thierbach & Petschick 2014). On two different days, attention was to general everyday life in Águas Claras across fixed periods of time (once at noon and once in the late afternoon). During the walk-through, attention was paid to situations demonstrating people supplying themselves with food or medical care. Those places where such actions took place were photographed. In order to be able to better understand context, a description of the situation as well as personal thoughts on the situation were noted for each photo taken in field. After the fieldwork, the photos were numbered, the handwritten notes were digitised, and the locations of the photographs were mapped.

Expert interviews

Some semi-structured qualitative interviews or expert interviews were conducted at the beginning of the stay in order to give the best possible overview of the situation in Brasília and the topic areas. This form of interview belongs to the interpretative-understanding methods and is guided by non-standardised questions. The fundamental steps of an expert interview are as follows: selecting the experts, contacting them, establishing guiding questions, conducting the interview, evaluation, and interpretation of the results (Pfaffenbach 2011; Reuber & Pfaffenbach 2005). In the context of this research project, a total of eight expert interviews were conducted - some in person, some online in video conferences. The organisation and selection of the interviewees was done in advance by Mauro Pires, Martin Coy and Tobias Töpfer. No expert interviews were conducted in the classical sense, as the experts presented their areas of expertise in the form of a lecture, and then the individual groups asked their subject-specific or topic-specific (leading) questions. The questions were geared exclusively towards providing concrete answers to the research questions. In this way, it was possible to collect sufficient material for a comprehensive overview of the topic and to partially answer the research questions. The interviews or the excerpts relevant to the group were transcribed and processed using the analysis software MAXQDA. A coding guide was created, and the statements of the interviews were assigned accordingly. Both in the transcription and in the evaluation, however, it was not the statements of the experts themselves that were used, but the summarised translations by Martin Coy.

All illustrations, graphics, tables and photos used in connection with the topic Daily Life: Águas

Claras as well as the present text were

created or taken by Lisa Maria Eß, Richard Matalewski and Sophia Märk.

References

Batinic, B. (2003): Internetbasierte Befragungsverfahren. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 28 (1): 6-18.

Borsdorf, A. & Bender, O. (2010): Allgemeine Siedlungsgeographie. Böhlau Verlag, Wien, Köln, Weimar.

Costa, C. & Lee, S. (2019): The Evolution of Urban Spatial Structure in Brasília. Focusing on the Role of Urban Development Policies. Sustainability, 11 (2): 553–573. Link

Coy, M. & Pöhler, M. (2002): Condomínios fechados und die Fragmentierung der brasilianischen Stadt. Typen-Akteure-Folgewirkungen. Geographica Helvetica, 57 (4): 264–277. Link

Glasze, G. (2011): (Un-)Sicherheit und städtische Räume. In: Gebhardt, H.; Glaser, R.; Radtke, U. & Reuber, P. (eds.) Geographie. Physische Geographie und Humangeographie. 2. Auflage. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg: 885–893.

Glückler, J. (2011): Wirtschaftsgeographie. In: Gebhardt, H.; Glaser, R.; Radtke, U. & Reuber, P. (eds.) Geographie. Physische Geographie und Humangeographie. 2. Auflage. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg: 912–951.

Governo do Distrito Federal (2019): PDAD 2018. Pesquisa Distrital por Amostra de Domicílios.

Heineberg, H. (2001): Grundriß Allgemeine Geographie. Stadtgeographie. Schöningh, Paderborn.

Heineberg, H. (2007): Einführung in die Anthropogeographie/Humangeographie. Schöningh, Paderborn.

Heineberg, H. (2011): Stadtgeographie. In: Gebhardt, H.; Glaser, R.; Radtke, U. & Reuber, P. (eds.) Geographie. Physische Geographie und Humangeographie. 2. Auflage. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg: 856–909.

Kagermeier, A. (2011): Verkehrsgeographie. In: Gebhardt, H.; Glaser, R.; Radtke, U. & Reuber, P. (eds.) Geographie. Physische Geographie und Humangeographie. 2. Auflage. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg: 1045–1061.

Kainrath, W. (1997): Die Bandstadt. Städtebauliche Vision oder reales Modell der Stadtentwicklung? Picus Verlag, Wien.

Leser, H.; Egner, H.; Meier, S.; Mosimann, T.; Neumair, S.; Paesler, R. & Schlesinger, D. (2011): Diercke Wörterbuch Geographie. Raum - Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft - Umwelt. Westermann, Braunschweig.

Meier Kruker, V. & Rauh, J. (2005): Arbeitsmethoden der Humangeographie. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt: 90-107.

Partzsch, D. (1964): Zum Begriff der Funktionsgesellschaft. Mitteilungen des deutschen Verbandes für Wohnungswesen, Städtebau und Raumplanung (4): 3–10.

Pfaffenbach, C. (2011): Methoden qualitativer Feldforschung in der Geographie. In: Gebhardt, H.; Glaser, R.; Radtke, U. & Reuber, P. (eds.): Geographie. Physische Geographie und Humangeographie. 2. Auflage. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, München: 157-175.

Reuber, P. & Pfaffenbach, C. (2005): Methoden der empirischen Humangeographie. Beobachtung und Befragung. Westermann, Braunschweig: 128-139.

Sampaio Silva, M. A. (2016): A especulação imobiliária descaracterizando uma idea. O caso de Águas Claras, no DF. Link

Saurer, H. & Rosner, H.-J. (2011): Von Mercator zur virtuellen Welt. In: Gebhardt, H.; Glaser, R.; Radtke, U. & Reuber, P. (eds.): Geographie. Physische Geographie und Humangeographie. 2. Auflage. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, München: 190-198.

Thierbach, C. & Petschick, G. (2014): Beobachtung. In: Baur, N. & Blasius, J. (eds.): Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung. Springer Fachmedien, Wiesbaden: 855-866. Link

Werlen, B. (2008): Sozialgeographie. Eine Einführung. Haupt Verlag, Bern, Stuttgart, Wien.Link